The State of Sewage: Are We Flushing Away Our Future?

Contents:

- Sewage, the Environment and the Threat to Biodiversity

- Sewage in the Sea and the impact on Marine Life

- The Effect of Sewage on the Earth

- World Sanitation Risks from Raw Sewage

- Fatbergs and Blocked Sewers

- What Causes Fatbergs?

- Why is there a Need for Sewer Divers in India?

- Sanitation and Rescuing the Future

- What Not to Flush

- The Attenborough Effect

- Septic Tanks and Off Mains Drainage Solutions

- How the Septic Tank Works

- Environmental Responsibility Begins at Home

Water pollution is a critical concern, for the United Kingdom and across the globe.

Human beings have contaminated their drinking water for centuries without realising it, but this contamination increased significantly with the industrial revolution, during the 19th century, as factories released pollutants into rivers, lakes and streams.

In the 21st century, water pollution has entered a new age of extremes. Greenpeace has reported that 70% of China’s lakes and rivers are now polluted from industrial waste.

Marine pollution is also on the rise, with raw sewage from coastal countries and pollution from boats contributing to the destruction of sea-life, and the damage to essential ecosystems.

Giant fatbergs routinely clog up our sewers and drainage networks.

There is a growing awareness of the need to tackle water pollution, but some of the things we can do to make a difference are very much at local level. This is about how we use and dispose of our waste.

The flushing toilet has become a familiar feature of a clean, convenient way of life, but are we at risk of flushing away more than we bargained for and putting the future in peril?

We flush away 3.4 billion wet wipes each year.

This is about considering the impact of our waste, and understanding the best solutions for our individual lifestyles and circumstances.

These solutions include raising awareness of environmental impact, changing behaviours and installing the right drainage solutions to meet our needs but also to protect the environment for the future.

Sewage, the Environment and the Threat to Biodiversity

What should we do with our waste? This is an ongoing problem we all face, and the consequences for the environment are serious.

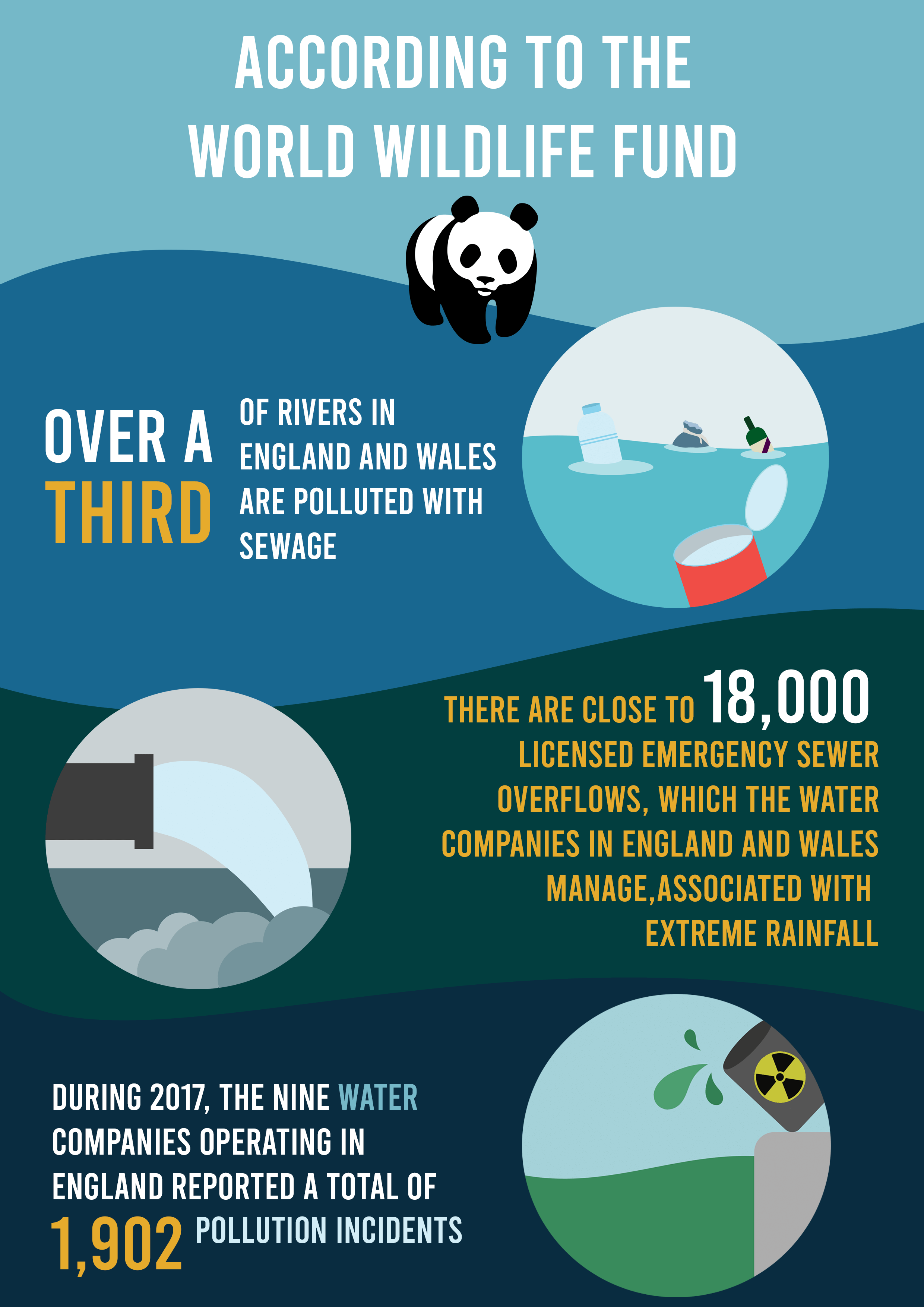

According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF):

- Over a third of rivers in England and Wales are polluted with sewage.

- There are close to 18,000 licensed emergency sewer overflows, which the water companies in England and Wales manage, associated with extreme rainfall.

- During 2017, the nine water companies operating in England reported a total of 1,902 pollution incidents.

The problems run deep. Continuous, legal discharges into rivers from sewage treatment centres are not of a high enough standard to protect rivers, according to WWF. Alongside these discharges are multiple failings leading to further pollution.

The situation is exacerbated by extremes in rainfall, and by people flushing items such as cooking fat, wet wipes, cotton buds and sanitary products down toilets. The drainage and sewage networks cannot cope.

The number of healthy rivers in the UK is in decline, from 27% in 2010 to 14% in 2017. At this rate, there will be no healthy rivers left by 2025.

The risks to human health are considerable. Untreated sewage contains parasites, pathogens and bacteria, including E coli and salmonella.

There are serious and sometimes fatal diseases linked to sewage pollution, such as septicaemia, hepatitis A and leptospirosis.

Sewage pollution is also a threat to the biodiversity of freshwater environments. This covers all categories of freshwater habitats and, according to the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, some of the main sources of point pollution are pipes discharging effluents from wastewater treatment plants and sewage tanks.

WWF highlights river damage as one of the major threats to wildlife in the UK. Because so few of the country’s rivers are healthy, this poses a huge threat to a diverse range of wildlife, including kingfishers, river voles and numerous species of fish.

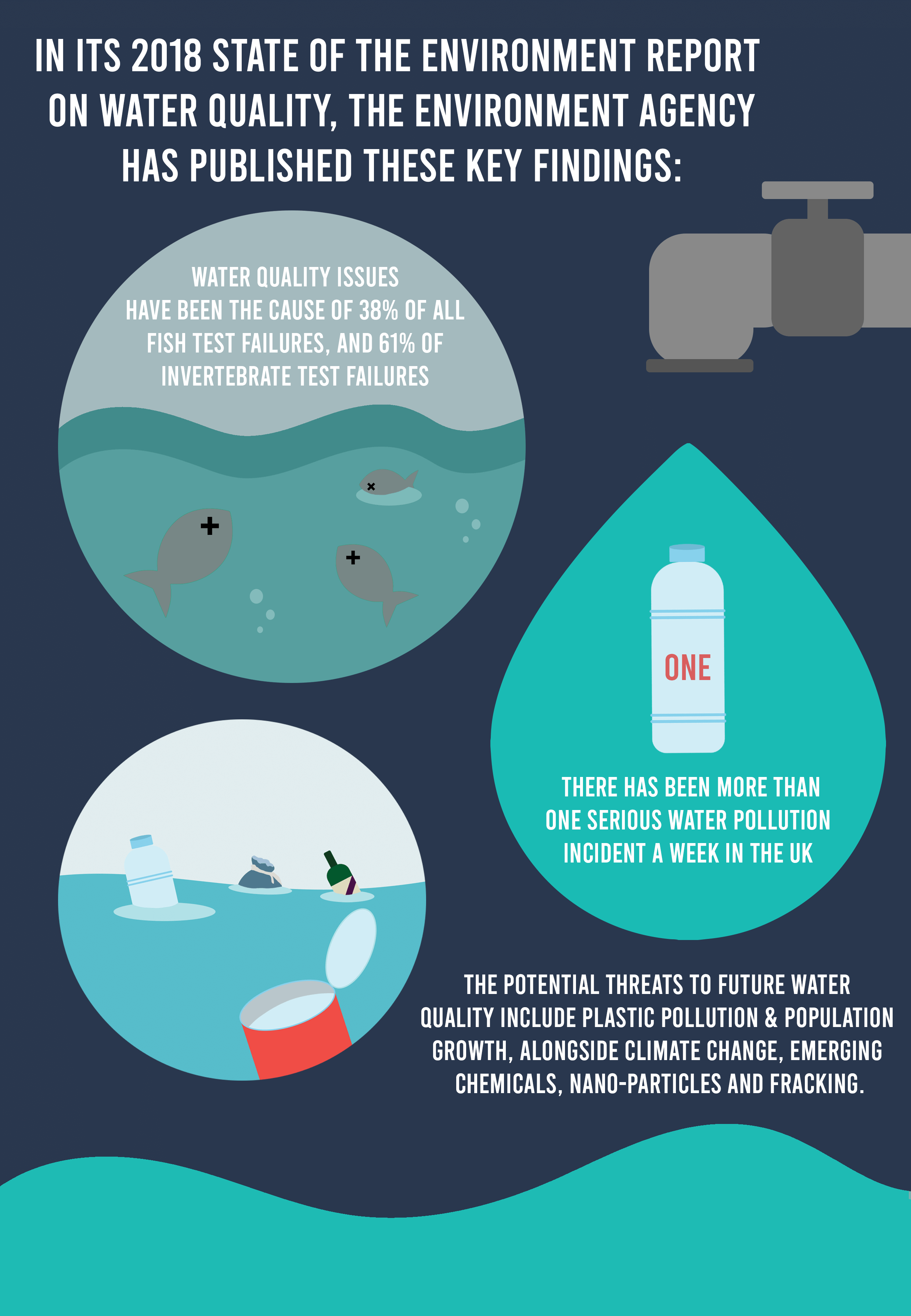

In its 2018 State of the Environment report on water quality, the Environment Agency has published these key findings:

- Water quality issues have been the cause of 38% of all fish test failures, and 61% of invertebrate test failures

- There has been more than one serious water pollution incident a week in the UK

- The potential threats to future water quality include plastic pollution and population growth, alongside climate change, emerging chemicals, nano-particles and fracking.

Sewage in the Sea and the impact on Marine Life

Seabirds can have their stomachs full of plastic items, and plankton consume microplastics polluting the oceans, passing this back up the food chain. Marine life is under threat.

Plastics along with other waste are choking the seas.

Many boats will typically have toilets that pulverise the waste before pumping it out into the sea. But while this means there are no visible solids in this waste, it still contains large amounts of nutrients and bacteria, contributing to health problems and to pollution.

Two major changes associated sewage pollution in the sea are:

- Deoxygenation – the loss of oxygen in the ocean

- Turbidity – increased cloudiness.

The consequences of these changes include the disease, suffocation and death of fish and other forms of marine life. There is also long-term damage to ecosystems and the build-up of toxic materials in the food chain.

There are many countries now where the seawater is not safe for bathing or fishing in.

The Effect of Sewage on the Earth

Sewage can have a very direct impact on aquatic ecosystems and on marine life but it also has an effect on the earth in general.

If raw sewage, as wastewater, gets into groundwater or other water supplies, it can cause damage across the entire ecosystem.

We have already mentioned the threat to human health and to fish and other marine life, but there are also long-term dangers to food and crops.

Untreated wastewater is often used to irrigate crops and farms, but it can contain heavier concentrations of various metals than treated water. If these metals get into the soil, plants will then consume them. This contamination may happen slowly over time and therefore be difficult to detect.

World Sanitation Risks from Raw Sewage

The United Nations General Assembly recognised access to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right in 2010. But the sanitation risks from raw sewage remain on a global scale.

- The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that two billion people do not have access to basic sanitation facilities such as toilets. This includes 670 million people who still defecate outside, in ditches, for example, or into open bodies of water.

- Of the world’s population, an estimated 10% consumes food that is irrigated by wastewater.

- Diseases such as cholera, dysentery, typhoid, polio and hepatitis are all linked through poor sanitation, which increases their spread.

- Poor sanitation is responsible for over 430,000 diarrhoea-linked deaths annually.

- Diarrhoea is a major killer, but it is preventable, with better sanitation and water and improved hygiene. These measures could prevent the deaths of 297,000 children under five, each year.

Fatbergs and Blocked Sewers

Fatbergs make the headlines because they are a tangible and imposing reminder of the damage plastics and other waste can do when they become part of sewage.

They are costly to clear up, and they could also cost in terms of human health.

The UK spends around £100 million annually clearing up an estimated 300,000 fatbergs.

A test on a London fatberg found under the south bank has revealed that it was made up of 90% cooking fat, but also contained potentially infectious bacteria such as listeria and E coli.

While this bacteria only poses an immediate threat to people working in sewers, it could, in theory, make its way into households and businesses should there be flooding.

The most notorious fatberg to date was in east London, weighing in 130 tonnes and 250 metres in length.

To put this into perspective, that makes it longer than Tower Bridge by 10 metres, and weighing the equivalent of 19 elephants or two Airbus aircraft.

What Causes Fatbergs?

Fatbergs are giant masses of congealed oil, fat, grease and debris that build up in sewers.

Typically, they contain items which are not designed to be flushed down the toilet or drain, such as wet wipes, cotton wool buds and nappies.

The combined effect of single-use plastic items with solidified fat causes an accumulation of solid mounds of waste, which can eventually block sewage systems.

This build-up comes from a reaction of calcium with fat and grease, which have broken down to release saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. These combined deposits then coat the inside of pipes and start to build mass from there.

Whereas in the UK, London-based fatbergs have been prominent in the news, the problem is worldwide, occurring wherever people put oils and fats into a drainage system.

Clearing sewers can be highly hazardous too, as the experience of India’s sewer divers demonstrates.

Why is there a Need for Sewer Divers in India?

In major cities in India, such as Delhi and Mumbai, thousands of people make their living cleaning sewers by hand, doing what is known as manual scavenging.

Being a so-called sewer diver is one of the deadliest occupations in the world.

They clean sewers and septic tanks without wearing any kind of protective clothing or equipment.

According to the Delhi cleaners commission, almost 70% of manual scavengers die while carrying out their work.

Officially, India banned this kind of work as far back as 1993, but government agencies throughout the country still use manual scavengers to clean sewer systems and drains.

There various driving forces behind this: the haphazard growth of urban areas; the underfunding of sanitation; and the caste system.

Many Indian cities are places of extreme contrast in wealth and poverty, with growth from illegal settlements leading to a proliferation of slums. At the same time, access to sanitation services has been monopolised by better off residents. Government funding has not been able to keep pace with urban growth, leading to underfunding of sanitation.

As in other urban concentrations globally, the pressure on sanitation is immense, and, unfortunately, the solution to managing it is very human, rudimentary and dangerous to those involved.

The other contributing factor to the continuing use of sewer divers is the Indian caste system.

Most manual scavengers are from a single caste, the Valmiki. They are at the bottom of this intricate system, which controls who Indians marry and even what food they eat.

Within the Valmiki caste there is a gender divide when it comes to manual scavenging. The men clean the sewers, while the women clear the holes used as toilets from house to house.

It is often lethal work which, under the caste system, the Valmiki are born to do.

Sanitation and Rescuing the Future

Any sanitation system, however sophisticated, must rely to an extent on its users for its success.

The future of sanitation and water is tied up with the future of the planet itself.

The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) points out that:

- 5.2 billion people will need better sanitation by 2030

- As demand increases for water, supply will become more variable

- Quality of supplies will matter as much as quantity

- Migration and conflict will be closely linked to water stress or water scarcity

- Sanitation can unlock growth within countries, improving water quality and safety and helping generate jobs, creating more than just health benefits.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has highlighted the global challenge posed by unsafe sanitation.

With over half the world’s population, around 4.5 billion people, with unsafe sanitation, or with none at all, there is a continued threat to life from waterborne diseases.

The problem is becoming more urgent due to population increases, urbanisation and water scarcity.

The future will require innovative solutions in sanitation and managing wastewater. The challenge will be how to introduce new infrastructure into concentrated urban settings, especially where unmanaged settlements have contributed to this population density.

One focus will be on sustainable approaches to wastewater management.

The United Nations University has reported on a recent study in Uganda, involving marketing biogas and fertiliser made from wastewater products. The study suggests that this approach could run a cost recovery sanitation system to meet the needs of 400,000 people.

This process uses a device known as a digester. It is a sealed container within which bacteria break down organic material. At the end of this process comes an odour-free liquid that acts as an easily absorbable, rich fertiliser that is free from pathogens.

Alongside the development of these durable, self-sufficient technologies there must also be action closer to home.

This starts with the basics, of what not to flush.

What Not to Flush

We have talked about the effects of flushing certain materials and items down the toilet and drains.

Some manufacturers of wipes, for example, state that these items are safe to flush down the toilet. But while some are marketed as biodegradable, they can contain plastic resins such as polypropylene and polythene alongside cotton and rayon.

They may, in fact, take months to decompose. In the meantime, they add to the bulk of waste that is clogging up sewers and drains.

Wipes may also have a further environmental impact, where marine life mistake them for food, which then results in plastics making their way into our food chain. The health consequences of this may yet be unknown, but they could be cumulative.

Water UK has launched a Fine to Flush campaign in the fight against fatbergs, which aims to identify any wet wipes which can easily be flushed.

However, the best, safest approach, is not to flush them at all.

Here is a checklist of items and materials not to pour down the drain or flush down the toilet

- Baby wipes

- Tampons and sanitary towels

- Cotton wool buds and pads

- Nappies

- Cooking fats and oils

- Paints and white spirit

- Weed killer and gardening chemicals

- Anti-freeze and brake fluid

- Motor oil

- Cleaning rags

- Medicines.

While some detergents and washing and cleaning chemicals may be poured away or flushed, using excessive amounts of them can also cause blockages.

It is a case of people changing their behaviours.

One driver of change in behaviours and attitudes towards the environment has come from an unexpected source, the respected and much-loved broadcaster, Sir David Attenborough.

The Attenborough Effect

Following the transmission of the BBC’s Blue Planet II series, there has been a reported plummet in plastic pollution.

In the highly anticipated and widely watched sequel to the original Blue Planet series, Sir David Attenborough raised awareness of the impact human beings are having on the planet, highlighting the damage to marine ecosystems from plastics and other waterborne pollutants.

The series’ final episode was Sir David Attenborough’s call to action. It showed how the producers of the show had found plastic in every part of the ocean they explored, however remote.

Earlier in the series, footage of a whale carrying a calf for days after it had died, poisoned by plastic in the mother’s tainted bloodstream, had a huge impact on audiences.

While some of the material was hard-hitting, the message that resonated with audiences afterwards was a positive one: to act now.

- Following the transmission of Blue Planet II, a GlobalWebIndex report recorded 53% of people surveyed cutting their amount of single-use plastic over a 12 month period.

- The same research found that 82% of people in the UK said they valued sustainable packaging because it could help protect the environment.

- Immediately after the last episode of Blue Planet II , there was a surge in online searches for plastic recycling and a huge jump in traffic to the Marine Conservation Society website of 169%.

Audience figures for Blue Planet II indicate that it topped the ratings in the UK in 2017. It’s first episode alone attracted over 14 million viewers.

These viewers will come from a variety of backgrounds and living conditions, but what might unite them is a responsible, practical, forward-thinking approach to their own water usage and sanitation.

Septic Tanks and Off Mains Drainage Solutions

Not every property has easy access to the mains sewer system. As developments spread in response to housing demand, so more properties are having to make arrangements for off mains drainage.

As we have shown, safe, responsible disposal of wastewater is critical for both the environment and public health.

Without a septic tank, there can be a build-up of wastewater and effluence around a property. This can result in hazardous conditions, with the potential for toxicity to spread.

Septic tanks are, therefore, an essential solution to off mains drainage and wastewater disposal.

How the Septic Tank Works

The septic tank is an evolutionary leap forward from the traditional cesspit. Whereas the cesspit is a holding tank for waste, with no outlet or means of treatment, the septic tank is designed to separate solids, oils and grease from liquids.

This is a natural, biological process, producing clarified water for discharging back into the ground. It depends on the subsoil of a drainage field being capable of receiving this discharge of fluid and percolating it.

The system has certain environmental benefits too, for commercial properties looking to recycle their wastewater.

With many of the UK’s sewage systems seriously overstretched, as the fatberg phenomenon demonstrates, it makes sense to look for ways of reducing the demand on this network.

Septic tanks are environmentally friendly because they use a natural filtration system to recycle water. There are no chemicals involved. Instead, naturally occurring bacteria breaks down the waste. It then recycles clarified water back into the environment.

Compared to other treatments and pipe systems, septic tanks are cost-effective, and they give independent control to the owner, without them having to rely on the waste disposal services of a sewage company.

They are low maintenance with considerably lengthy lifespans of up to 40 years or more.

Just as the septic tank itself marks a big leap forward from the traditional cesspit, so modern sewage treatment plants represent a significant step up in terms of design and operation.

Nowadays, sewage treatment plants deliver efficient, localised waste disposal while complying with tough new regulations, to ensure the protection of the surrounding environment.

Sewage Treatment Plants must have BS EN 12566-3 certification, indicating that they meet rigorous standards for packaged underground sewage treatment.

The term septic comes from the tank’s bacterial environment.

Anaerobic bacteria are microorganisms that digest the nutrients in organic materials, and this process converts nitrogen into ammonia and organic acids.

However, while these bacteria are resilient and can withstand environmental changes, on their own they are not the most efficient means of breaking down waste.

Therefore, by using a septic aerator, the tank promotes the growth of aerobic bacteria too, for added protection against pathogens and contaminants in the wastewater it processes.

Together, the anaerobic and aerobic bacteria create the optimum septic environment.

This is a versatile, environmentally friendly means of providing bespoke sewage treatment solutions to both domestic and commercial premises.

Environmental Responsibility Begins at Home

Sometimes the environmental picture can seem immense, with issues to do with climate change and world sanitation almost too big to grasp.

However, we believe that environmental responsibility is also an individual issue, about the choices we each make, in our own homes and workplaces.

Waste disposal matters as much at this level as it does globally, if we are all going to work together to protect our future.

For more information about septic tanks, sewage treatment and drainage solutions, please contact OMDI.

Phone 01977 800 418, email enquiries@omdi.co.uk, or please complete our online contact form and we will be in touch as soon as possible.